|

John Hunt - Norfolk Bird Man

(1777–1842)

John Hunt is a largely forgotten figure today and yet British Ornithology, which he wrote, illustrated, printed and published in Norwich in three volumes between 1815 and 1822, is one of the earliest and most ambitious attempts to describe and illustrate the entire wild bird species of the British Isles.

Ancestry and birth

The only substantial study of his life, by Captain Sir Hugh Steuart Gladstone, was published in the journal British Birds in 1917. While Captain Gladstone gathered a good deal of biographical information that might otherwise have been lost, Hunt's ancestry remained obscure.

Researching his life only 75 years after his death, Gladstone found that Hunt’s family background, date and place of birth were not known with any certainty, even by his grandson, Arthur Robert Grand, whom he met and interviewed. When Hunt died in America in 1842 some newspaper obituaries gave his age as 65, others 67, making his birth year sometime between 1774 and 1777. Although Arthur Grand believed his grandfather had been born in Wymondham in 1777, the weight of evidence, including a statement by one of Hunt’s contemporaries, the antiquarian John Stacey, supports the theory he was ‘a Native of Norwich’. A pencilled note in a copy of British Ornithology once owned by Russell James Colman and now in the possession of the Norfolk & Norwich Library reads: ‘John Hunt, born in the parish of St Augustine’s, Norwich’. Unfortunately, no one named John Hunt appears in St Augustine’s baptismal register from the relevant period. However, a neighbouring parish, St Clement’s, does record that a John, son of John and Rebecca Hunt, was baptised there on 2 November 1777, the natal year Hunt’s grandson believed correct.

A trawl though Norwich parish records of the second half of the 18th century reveals that a John Hunt was married to a Rebecca Brown at St Stephen’s church on 24 August 1766. There is a strong probability that they are the same John and Rebecca recorded as the parents of John Hunt in St Clement's baptismal register for 1777 as no other couples named John and Rebecca Hunt can be found in Norwich marriage or baptismal records of this period. Subsequently, the children of John and Rebecca Hunt can be traced in the records of several Norwich parish. First, Rebecca, baptised at St Stephen’s church on 16 August 1767. Then a John, who perhaps died in infancy, was also baptised there, on 3 February 1771. Six years later, in 1777, another John (our man?), baptised at St Clement’s church, and finally Samuel John, baptised at St Augustine’s church on 23 December 1781.

Appearance and family background

Writing after John Hunt’s death, a contemporary – fellow avian specimen collector, Joseph Clarke of Saffron Walden in Suffolk, recalled meeting Hunt in the home of Dr Griffin, a surgeon and secretary to Norwich Museum:

‘I recollect the man Hunt perfectly well,' Clarke wrote. 'I understood he was a weaver; he was below the middle height, thin, pale, consumptive looking.’

Hunt’s biographer, Captain Gladstone, betraying a touch of Edwardian snobbery, dismissed the suggestion that Hunt was a weaver as ‘not worthy of any serious attention’, and yet research among Norwich records does indeed suggest he came from a weaving family. The baptismal records noted above show that the Hunt family moved from St Stephen’s parish in the mercantile centre of Norwich to the textile-manufacturing north of the city (St Clement's and St Augustine's) sometime between 1771 and 1777. The will of one John Hunt, ‘a weaver of St Augustine’s’, proved in Norwich Consistory Court in 1807, may very well be that of his father. It is not impossible, therefore, that John Hunt junior may have served an apprenticeship in weaving in St Augustine’s parish under his father. The skills he would have learnt would be useful to him later, particularly when he became a printer, but weaving was not destined to be his metier.

Marriage and bookselling

In 1801, seemingly out of no where, John Hunt, aged just 24, appears in the Norwich Poll Book (a register of those men entitled to vote in local and national elections) as a stationer and bookseller as well as a freeman of Norwich. How had the son of a weaver, himself possibly an apprentice weaver in his youth, risen so high and so fast? The answer is probably that in addition to his intelligence, skill and industry, he had the good fortune to marry well. His wife Elizabeth Harper was quite a catch. A cousin of Sir John Harrison Yallop (1762–1835), a wealthy merchant who would be elected Mayor of Norwich in 1815 and 1831, she brought with her a dowry of £3,000, a considerable sum in those days and more than enough to set her husband up in business. They were married in St Peter Mancroft church (the bride’s and Sir John Yallop’s parish church) on 12 December 1799. The register records John Hunt as being of the parish of St Augustine’s, which corroborates his connection with this parish noted in the Russell James Colman copy of British Ornithology mentioned above.

After marriage John and Elizabeth Hunt set up home, which was also their business premises, at 12 Redwell Street in the parish of St Michael at Plea, an area of the city long associated with printing. In the 1802 Norwich Poll Book, John Hunt, bookseller, is still listed here, and in those days before secret ballots we can see that he supported the Whig candidate. Thirty years later he was still a staunch supporter of the Whigs, at a time when revolution abroad and the clamour for parliamentary reform at home often turned the rivalry between Whigs and Tories into violent clashes, particularly at election time, and in one such riot, shortly before emigrating to America, Hunt was attacked and injured.

According to the Hunt family Bible, seen by Captain Gladstone in 1917, John and Elizabeth’s first child, John, was born on 11 March 1801 and baptised with their second child, Samuel Valentine (born on St Valentine’s Day,

14 February 1803) at the church of St Michael at Plea on

8 January 1804. A third child, Charlotte, was born on

5 September 1804 and Eliza (Hunt's nephew Alfred Grand’s mother) on 1 December 1806. No record has yet been discovered of their christening. In about the year 1809 Hunt moved with his growing family to the town of Beccles in Suffolk, where he opened a seminary for young ladies; a profession he would return to in America more than twenty yeas later. It was probably here that three more children were born: George on 18 June 1809, Mary Anne on 3 April 1811 and Alfred on 6 August 1813. Shortly after this an outbreak of ringworm forced the closure of the school and he came back to Norwich sometime before 1815.

British Ornithology

On returning to Norwich the Hunt family settled in a house with a large garden near the junction of Rose Lane and

St Faiths Lane close to the Foundry Bridge, opened in 1811, in what is now part of Prince of Wales Road. It is difficult now to imagine the rural vista that Hunt would have enjoyed, decades before Thorpe Railway Station was built just across from him on the opposite bank of the the River Wensum. The garden had willow trees which bordered the river and in his garden he sometimes saw ‘Little Woodpeckers’ (presumably the fairly uncommon, sparrow-sized Lesser Spotted Woodpecker), which crossed the river from the slopes of Thorpe Woods to drum in his willows.

It was here that he embarked on his magnum opus British Ornithology, or to give it its full title British Ornithology: containing portraits of all the British birds, including those of foreign origin: with descriptions compiled from the works of the most esteemed naturalists, and arranged according to the Linnean classification. With this work Hunt intended to record, for the first time, in word and picture 250 of the native, vagrant and foreign-established wild bird species of the British Isles. He didn’t quite succeed, though he managed to describe about 220 species and to produce 180 hand-coloured plates, as well as at least eight uncoloured plates and four anatomical plates almost single-handedly in under seven years, no mean feat. Only three out of the projectd four volumes were ever produced, and volume 3 is unfinished, the text ending mid-sentence followed by 76 plates without text.

In an age before cameras and field glasses he worked mainly from dead specimens brought to him by other collectors or purchased from local wildfowlers and sportsmen. In common with many naturalists of that era he seems to have had no ethical dilemma in encouraging the shooting and trapping of birds, some of which he admitted were very rare. The countrymen who supplied his specimens also no doubt provided him with many of the curious local names for birds that he recorded, such as Arsefoot (Little Grebe), Coal and Candle Light (Pintail Duck), Coddy Moddy (Common Gull), Gillihawter (Barn Owl), Market Jew Crow (Chough), Puttock (Magpie), White Whiskey John (Shrike), and Yappingale or Yaffle (Green Woodpecker).

One of the chief claims for the important of his published work in the annals of British ornithology is that it was the first to record a number of birds rare to these shores, including the Red-crested Pochard (Netta rufina), the Arctic Warbler (Phylloscopus borealis) and the Caspian Tern (Sterna caspia). Though Hunt had in fact mistakenly identified some of them as their commoner native cousins, his meticulously detailed paintings allowed later ornithologists to correctly identify them. In some instances he seems to have resorted to plagiarism. His illustrations of the White-tailed Eagle, for example, were copied from Thomas Bewick’s History of British Birds (published between 1797 and 1804) and then printed in reverse. Perhaps specimens were unavailable and the pressure of producing such a vast undertaking led him to occasionaly cut corners.

The first volume of British Ornithology was published in Norwich in 1815, by which date he had moved house again, this time to Red Lion Street. It may have been here that John and Elizabeth’s eighth and final child, Julia Eliza, was born on 28 October 1815. The publication of British Ornithology was a complex, expensive and risky business venture, as well as a scientific and artistic tour de force. All of the plates were engraved on copper by Hunt himself, and then hand-coloured, some by him and some by his second son, Samuel Valentine Hunt (1803–1895), based on his father's detailed notes on plumage as well as his taxidermy specimens.

By the mid-1820s the third, unfinished, volume had been printed but the project then stalled through lack of subscriptions, leaving Hunt severely out-of-pocket. In 1826 he corresponded with Sheppard and Whitear, compilers of the ‘Catalogue of the Norfolk & Suffolk Birds’, and in 1829 he contributed a list of 230 birds to Stacey’s General History of the County of Norfolk, ending with an advertisement for his shop in the parish of St Stephen’s, Norwich, where he had ‘a large collection of British birds for sale, some of which are exceedingly rare’, meaning stuffed rather than live birds. In the same year he was listed as a mace bearer to the mayor of Norwich, a ceremonial job which he may have taken in order to supplement his dwindling income from his taxidermy business. Meanwhile, he continued to move around the city. In the 1830 Poll Book he is registered as an engraver in Bridewell Alley, Norwich, but by 1832 he had moved again, to the top of Orford Hill, where a close friend, John Skippon, also lived. Two years later, seeing no prospect of being able to make a living in England, he decided to emigrate to America, no small undertaking for a man of slender means, then in his late fifties and not in the best of health.

America

His ship set sail from England on 1 August 1834. Accompanying him were his wife Elizabeth and three of their eight children, second son Samuel Valentine, aged 31, and his two youngest daughters, Mary Ann, 23, and Julia Eliza, 18. His youngest son, Alfred, then aged 21, joined them in America later. Two months after arriving in America Hunt wrote a long letter to his Norwich friend John Skippon, detailing the events of their arduous voyage and the sights and sounds of New York that assaulted them on their arrival. This was published in Norwich in 1835.

They had left England full of hopes and fears. The sailors were full of dire predications of a bad crossing because there were two missionaries on board, a bad omen, reflecting the mariners’ superstition that men of religion ("Jonahs") brought bad luck. All went well until the first day of September when a severe gale blew up. During the storm three of the crew were almost washed over board. By the time the storm had blown itself out the ship had been carried 500 miles south of their intended course. Further misfortune befell them when they finally arrived in New York three weeks late. Their ship was quarantined as cholera had been found on several vessels that had arrived just before them. When they were finally allowed to disembark several days later it was late in the evening and they were forced to take lodgings in a house where there was a noisy Ranters’ temperance prayer meeting going on. Such displays of noisy evangelicalism were not to Hunt’s taste. He wrote, ‘We could get neither beer or spirits, which would have been a treat, we had, however, good coffee instead’. The next day he ventured out to buy provisions. Manhattan seemed immense and densely populated: ‘the number of coaches and omnibuses make it appear constantly in a bustle’. Food was plentiful, though by no means cheap. He noted that beer, which was extremely strong, was just as dear as in Norwich at 3d per pint. He was amused by the number of grey squirrels on sale for meat, but as they were cheap and he needed ‘some tippets for the females’, he bought a few, which he found tasted ‘superior to rabbit, though smaller’.

He wrote to Skippon: ‘At the spring I expect a situation at some distance from this place, where I hope, with my old woman, to be comfortable’.

By 1837 Hunt had set up as a schoolmaster in Huntington, Long Island, and seemed to be doing reasonably well. The school, according to a letter he wrote at this time, had 70 pupils, the largest number of scholars ever known in that town. Twenty of the boys were, he noted, as large as himself and he ‘fagged’ himself too much endeavouring to teach them, putting his already delicate state of heath under considerable strain. In June 1840 he wrote to his third son, George, in Norwich, ‘I am not quite the colour of the Indians but a few shades lighter and have lost since I left Norwich about 50 lbs of good flesh’. In need of funds, he asked his son to sell ‘the Birds and Copperplates I left behind … I do not regret that I have not to work for the Great Paupers and Pampered Priests.’ The ‘Birds and Copperplates’ he referred to were his beloved collection of stuffed birds and the engraving plates of British Ornithology. The book had not been a success. He had sold very few copies, probably not enough to recoup his expenses. The ‘Great Paupers and Pampered Priests’ were those worthies of Norfolk who had either failed to honour their promises to subscribe to his book or owed him money for the parts they had received. Today British Ornithology is one of the rarest ornithological books in the world: there are fewer than a dozen complete copies in existence. Perhaps this explains why Hunt is so little known.

Whether he took an interest in the native birdlife of Long Island isn’t recorded. Two years after writing the above mentioned letter to his son George he was dead. It was the appropriately titled Brooklyn Daily Eagle that first announced his death in Huntington, Long Island, on

14 June 1842. When the first volume of British Ornithology had been published in Norwich in 1815 it was the first ornithological work of any significance to have been produced in Norfolk for 200 years – since Sir Thomas Browne’s ‘Account of Birds found in Norfolk’. By the time he left England in 1834, Hunt’s style of bird illustration had been outmoded by the work of the great American naturalist, John James Audubon, who painted in a more naturalistic style, often from life, rather than from artificially posed, stuffed specimens. The final volume of Audubon’s massive Birds of America was published in Britain in 1838.

In a sense Hunt the ornithologist had already become extinct. The last plate he ever engraved, which he didn’t find time to colour and publish, was of the Great Auk, a large, Penguin-like, flightless bird, the last recorded individual of which was shot in Iceland in 1844, having outlived its illustrator by just two years.

Sources

Gladstone, Sir Hugh Steuart. 'John Hunt 1777–1842', in British Birds, vol. XI, No. 7, December 1917.

Hunt, John. British Ornithology, vols I, II and III (Norwich, 1815–22).

Hunt, John. ‘List of Birds’, in John Stacey’s A General History of the County of Norfolk, vol. I (Norwich, 1829), pp. lviii–lxxv.

Hunt, John. America. Copy of Letter Just Received from Mr. John Hunt … (Norwich, 1835).

Index of Wills Proved in the Consistory Court of Norwich 1751–1818 (Norfolk Record Society, 1969).

Letters of John Hunt and family (Norfolk Record Office, ref. MS 4345).

McLaren, S. J. ‘A hunt for Hunt: the birdman of Norfolk’, in Norfolk Roots, issue 4, March/April 2005.

Norwich Poll Books (various dates).

Seago, M. J. Birds of Norfolk (Norwich, 1967).

Text © Stuart J. McLaren, 2010

|

|

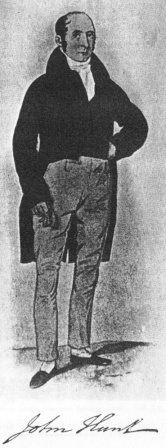

The only known portrait of John Hunt with a specimen of his signature

Below: Extracts from John Hunt’s 1829 ‘List of Birds’, selected for those that name

local collectors

Falco apivorus—

Honey Buzzard.

In the course of the last three years I have had five or six specimens of this rare and beautiful bird pass through my hands; one of them was taken alive on the estate of J. S. Muskett, esq. of Intwood, another on the estate of Sir Thomas Beevor; but the specimen now in the Norwich Museum, presented to that institution by the late lamented Mr. Whitear, is, perhaps the most elegant specimen (with respect to plumage) to be found in any collection.

Lanius ruficollis—

Wood Chat.

Mr. Scales assures me that he has killed this rare species in the neighbourhood of Beechamwell, where he has known it to breed and rear its young.

Oriolous Galbua—

Golden Oriole.

I have three specimens of this bird, killed in different parts of this county; and recently a fine specimen was shot at Hethersett, and is now in the possession of

J. Postle, esq. of Colney. The Rev Mr. Whitear, in a paper read before the Linnaean Society, says that “we have been informed that a pair of those birds built a nest in the garden of the Rev. Mr. Lucas of Ormesby, in Norfolk.”

Alca Alle—

Little Auk, is rare. Captain Cooper, formerly of North Walsham, once possessed a fine specimen, picked up near that town.

Procellaria pelagia—Stormy Petrel, Mother Carey’s Chicken.

For the last two years this bird has been numerous off the Yarmouth coast, where numbers have been taken.

Mr. J. Harvey, of that town, had, at one time, upwards of fifty specimens. In this winter before the last (1826)

a poor man caught one of these birds alive, in the Rose lane, in Norwich.

Ardea minuta—

Little Bittern.

One of these birds was shot by the gamekeeper of W. Jary, esq., of Burlingham, and is now in the possession of

W. Jary, junior, esq.,

of Blofield.

Motacilla provincialis—Dartford Warbler.

A pair of these elegant little birds was shot in the month of June, 1828; they are the only specimens ever found in this part of the kingdom, and are now in the possession of

Mr. Crickmer, of Beccles.

|