|

Matthew Brettingham the elder,

Norfolk Architect

[1699-1769]

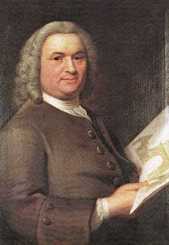

Matthew Brettingham the elder (right) is the most notable personage to be buried and commemorated in

St Augustine's church in Norwich.

Matthew Brettingham was born in Norwich in 1699, the son of Launcelot Brettingham (1664-1727) of the parish of St Giles. His mother's maiden name was Elizabeth Hillwell. His father's trade, that of bricklayer, was not quite as it is thought of today: he would have been in effect a jobing builder or stonemason, making his living repairing and altering buildings in Norwich. It was in this context that Matthew and his brother Robert learned their trade and it was from these relatively humble origins that Matthew rose to become one of the most important architects of the 18th century and a leading exponent of the Palladian style of architecture in England.

Working alongside their father Matthew and Robert thoroughly learnt the building trade and in 1719 both were made freemen bricklayers. Following Launcelot's death in 1727 Matthew began to seek commissions on a grander scale than could be found in Norwich. In 1734 he finally achieved his ambition when he was appointed Clerk of Works at Holkhaml on the north Norfolk coast. Holkham was the country seat of Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester. Work on his palatial mansion here had begun several years earlier under the supervision of the English Palladian architect William Kent and architectural theorist Lord Burlington. After Kent's death Brettingham had overall supervision of the work, seeing it through to completion just before his own death some thirty years later.

His role at Holkham Hall brought him other aristocratic commissions in East Anglia, including at Langley Hall (1740-6), Gunton Hall (1742) and Blickling Hall (1753-5) in Norfolk, and at Euston Hall (1750) and Benacre Hall (1763) in Suffolk. Other work in Norfolk included on Hanworth, Heydon and Honingham Halls, Lenwade Bridge (1741), St Margaret's church in King's Lynn (1742), the Shire Hall in Norwich (1747-9) and general repair work on Norwich Castle and Cathedral. Disputes with the City authorities over his work on the Shire Hall were to rumble through the courts for years and almost bankrupt him.

Outside East Anglia, he did much important work in London, including on the Duke of Norfolk’s and the Duke of York's townhouses, as well as at Lord Egremont’s Petworth House in Sussex, Baron Scarsdale’s Keddleston Hall in Derbyshire and other large country houses in Surrey, Sussex, Hertfordshire, Yorkshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire between the late 1740s and the early 1760s.

By the 1760s the Palladian style in which he had specialised had fallen out of fashion, surplanted by the Neo-Classical style of architects such as Robert Adam. Subsequently, Brettingham's aristocratic commissions dwindled and his money problems multiplied.

Matthew Brettingham's strong associations with

St Augustine's parish may have begun with his marriage to Martha Bunn, spinster of the parish, on 17 May 1721. All nine of their children were baptised in St Augustine's church. One of Brettingham's earliest recorded commissions was a dwelling house built near

St Augustine’s Gate in 1725. This was possibly for his own use as he also rented part of the nearby Gildencroft as a garden and orchard. He died in his own home in

St Augustine's on 19 August 1769 and is buried in a family vault in the north-east chancel aisle of

St Augustine's church. Two of his sons, Matthew Brettingham the younger (1725-1803) and Robert Brettingham became important men of business, Matthew as an architect, Robert as a manufacturer.

Matthew Brettingham the elder's memorial in

St Augustine's, which was probably designed by his son, Matthew Brettingham the younger, notes of him:

As a Man his Integrity,

liberal Spirit and benevolence of Mind;

endear'd him to all that knew his Virtues;

and his Talents as an Architect

to the Patronage and esteem of the Nobility,

the most distinguish'd

for their love of Palladian Architecture.

Despite achieving professional success he seems to have made little money. Matthew Brettingham the younger, who took over the family business following his death, said this was because was too honest: the implication being that many rich architects made their fortunes in bribes from contractors and by false accounting. Brettingham's reputation was however not quite as untarnished as his dutiful son made out. He frequently owed back rent on land he leased in St Augustine's from Norwich Corporation and was reputed to be a troublesome tenant. He is said to have set man traps in his orchard after wooden stakes supporting his espalliers were stolen. It has been noted that in his publication of The Plans, Elevations and Section of Holkham in Norfolk (1761) he singularly failed to mention the Hall's original architect: William Kent.

Text © Stuart J. McLaren, 2010 |

Matthew Brettingham,

the elder, seen here holding his design for a Triumphal Arch at Holkham Hall.

For more information on Matthew Brettingham the elder click here |