The Quakers and the Gildencroft

The religious and spiritual non-conformist movements in 17th-century England that led to the founding of the Society of Friends in 1667 had its origins in the 1640s; a time of civil war and political and religious ferment, when a group of radical Puritans, chief among them George Fox (1624-1691), unified a number of sects whose members sought a simpler form of Christian worship without clergy, churches or elaborate ritual.

The Friends or 'Quakers', as they were derisively known by their detractors because it was said they trembled and quaked with religious madness, first came to Norwich in 1654. From this date until the late 1680s, they suffered a great deal of persecution from those antagonistic to their form of religious life. Norwich Quakers during this period endured the breaking up of their meetings, beatings, seizure of their goods and imprisonment. At first their meetings were held in private houses and in the open air, such as on Mousehold Heath, or even in Norwich Gaol where many Friends were incarcerated in harsh conditions for long period awaiting trial.

Eventually, sufficient funds were raised to build a purpose-built meeting house in Goat Lane, which opened in 1679. As there were no public cemeteries at this period and the remains of those not baptised in the Established Church could not be interred in parish churchyards, non-conformists had to make alternative funeral arrangements for their deceased.

In March 1670 the Norwich Society of Friends bought an acre of land in the Gildencroft for £72 for use as a burial ground. Access was a major problem; coffins had to be carried on the shoulders of bearers along the then very much narrower Gildencroft Lane (now known as Quakers Lane) from St Martin’s Lane or via the even narrower Jenkins Lane also known as "Chafe Lug Alley" from St Martin's at Oak Street.

To alleviate this problem the Quakers paid an annual rent on a strip of land about 73 metres (80 yards) long between St Martin’s Lane and the Gildencroft Burial Ground just wide enough to allow the passage of a horse-drawn wagon bearing the coffin. A crescent was created outside the entrance to the burial ground and the Meeting House to allow the horse and wagon to be turned round after the coffin had been taken down for interment. This crescent still exists, while the route once taken by innumerable Quaker mourners can still be followed past the entrance to Malzy Court into overgrown land adjacent to the St Crispins Inner Ring Road.

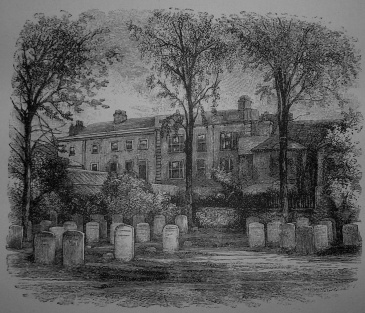

A gap between houses where this narrow carriageway once joined St Martin’s Lane can be glimpsed from here across the busy, four-lane road. Access to the Burial Ground was still problematic more than 150 years later, when in 1856 the Quakers bought premises in Pitt Street to give them an alternative entrance should their right to use of the St Martin's carriageway ever be lost. A 19th-century engraving (see right) shows the backs of houses in Pitt Street adjoining the burial ground. By 1906 access was no longer a problem and the Quaker's Pitt Street house was sold.

By the end of the 17th century Norwich had become one of the chief centres of Quakerism in England, with around 500 members in the city. Such was the press at their meetings in Goat Lane that it was agreed there was a need for a second meeting house. It was decided to build one in the Gildencroft on a plot of land adjacent to the west end of the burial ground. This land, which had been used for ‘taintors’ or frames for drying cloth and as a paddock for grazing horses, was bought from John Bound for £48 in August 1694. Work on the brick-built Gildencroft Meeting House was substantially completed by 1698 and the first meeting was held there on 19 February 1699.

By this period persecution of the Quakers had lessened considerably and the Friends now entered a period of quiet respectability. Arthur Eddington, chronicler of the first 50 years of the Quakers in Norwich, recorded the names of several of the Friends who attended meetings in the Gildencroft in the early 1700s, imagining the scene as they gathered in their new meeting house:

The deep hush of reverent worship settles upon the meeting, waiting in silent prayer until the Lord shall give a message to whomsoever. He shall choose. On the left hand side are the Quakeresses in their quiet garments, on the right the men Friends wearing their broad-brimmed hats, which will only be removed when one of their number shall voice their aspirations and desires in simple words of prayer.

Among those Norwich Quakers who would have been present in the early 1700s were Ursula Simons and Katherine Waymer, both elderly widows; Michael and Elizabeth Parker and their six children, John, Matthew, Michael, Nathaniel, Mary and Rebecca; Joseph Hadduck; Samuel Duncon; James Mayhew; Thomas Howard; John Cade; Henry Cannell; and John Gurney, a wool merchant, with his sons John and Joseph. Seated among the elders were some who had lived through the years of persecution, among them Alice and Edward Monk; John Defrance, the caretaker of the Gildencroft Meeting House; John Fiddeman and the ‘Father of the Meeting’ Thomas Buddery.

Noteworthy Quakers who would have attended meetings at the Gildencroft in the 18th century include John Gurney the Younger of St Augustine’s (1688/9–1741 ), son of John Gurney the Elder, the wool merchant mentioned above, who became known as the Weaver’s Friend for his defence of the Norwich worsted trade during a Parliamentary Committee in 1720; John Gurney the Younger's sons, John and Henry, who founded Gurney’s Bank, a direct ancestor of the present-day international banking business, Barclays, and whose first office was in Pitt Street in St Augustine’s; Mrs Elizabeth Fry, the famous prison reformer, a Gurney by birth, born in nearby Magdalen Street; her brother, the philanthropist and Quaker leader, Joseph John Gurney; and Mrs Amelia Opie, the Norwich-born poet, dramatist and novelist who is buried in the grave of her father, Dr Alderson,, in the northeast corner of Gildencroft burial ground.

On 4 Febuary 1798 William Savery, a noted Quaker elder from Philadelphia in the United States, spoke at the Gildencroft Meeting House. Among the assembled Friends was the 18-year old Elizabeth Gurney (later famous as the prison reformer Mrs Fry), who marked the words she heard this day as the true beginning of her religious life.

In 1826 a new, larger meeting house was built on the site of the original building in Goat Lane. This marked the beginning of a decline in attendance numbers at the Gildencroft. In the 1880s regular meetings were discontinued altogether and the building was let to the Baptist Congregation. In the 1890s the meeting house was turned over for use as an adult education school. The original building's end came during the 'Baedeker Blitz' on Norwich in April 1942 when incendiary bombs dropped by German bombers started a fire that burned out of control all night, gutting the entire building. The ruins then lay where they fell, a pile of overgrown rubble, until 1958 when the Meeting House was rebuilt, as far as possible using material salvaged from the debris, but on a much reduced scale. A plaque above the main entrance commemorates this.

In 1975 the rebuilt Meeting House was used by Norwich City Council as a day-centre for the elderly. Currently, it is used as a kindergarten by the Tree House Children's Centre. Quakers only meet here now on special occasions, usually for funerals or open air meetings in the adjoining burial ground.

The burial ground today is still a shady oasis of calm and is particularly attractive in spring when the daffodils and then the bluebells are in bloom. The headstones today all date from the 19th and 20th centuries. Almost all of those at the far eastern end of the Burial Ground bear the family name Gurney, one of the most prominent Quaker families in England. Hidden in the far left-hand corner alongside the Gurney graves is the headstone of the celebrated Norwich-born author, Amelia Opie, who was laid to rest in the grave of her father Dr Alderton in 1853.

For some unknown reason all the 17th and 18th century grave markers and tombs were removed many years ago, though the inscriptions on three of these were recorded in Blomefield’s History of Norfolk. Surprisingly, given the Quaker’s belief in plainness there was at one time at least one altar tomb, that of James Byar and his wife, Dinah, who died in 1716 and 1723 respectively. Among those know to have been buried there in the early 19th century was Ishmael Bashaw, a Turkish merchant and refugee whose memoirs are thought to be the first book published in England by a Muslim.

Text copyright Stuart J. McLaren |

|

|

|

Click on images below to see a larger image and read further information

Edwardian era postcard of the Gildencroft Quaker

Meeting House showing its original dimensions with two storeys. Note the rather staged "Quakeress" in bonnet and shawl.

19th-century engraving of the Gildencroft Quaker

Burial Ground looking towards the houses that then stood on the west side of Pitt Street.

19th-century engraving of the Gildencroft Quaker Meeting House.

The post-World War 2, rebuilt Gildencroft Meeting House on Chatham Street, now used as a kindergarten.

Entrance gate to the Gildencroft Quaker Burial Ground.

For more information on the Quaker community in Norwich

click here

For more information on the Gildencroft Quaker Burial Ground

click here |